Apartment size - how much space is enough?

Could you live in an apartment the size of a car parking space?

Last month approval was given for a new apartment block in Melbourne’s Brunswick which was just 24.5 square metres. That’s about the size of a double garage. That’s below the minimum apartment size for New York City (30 square metres) and London (37 square metres), prompting concerns over the proposed development.

I’ve lived in some tiny places by Australian standards, living in a studio-sized 49 square metre apartment with a toddler. I’ve always seen size as more of a design problem than a size problem. But even then, there are limits.

In last week’s post, we explored the growing trend of larger houses. The counter-trend is that apartment sizes are getting smaller. Is this the solution to the housing crisis? What are the health implications and how small is too small?

Read below for:

How minimum apartment sizes compare in major cities around the world.

The health implications of small apartments.

What’s required to create healthy homes that actually help solve the housing crisis - when is small too small?

Weekly Trend Update

Lifestyle trend: Apartment sizes are getting smaller, despite Australians living in some of the largest houses in the world. Over the past 15 years apartment size has decreased by almost 15% (ABS)

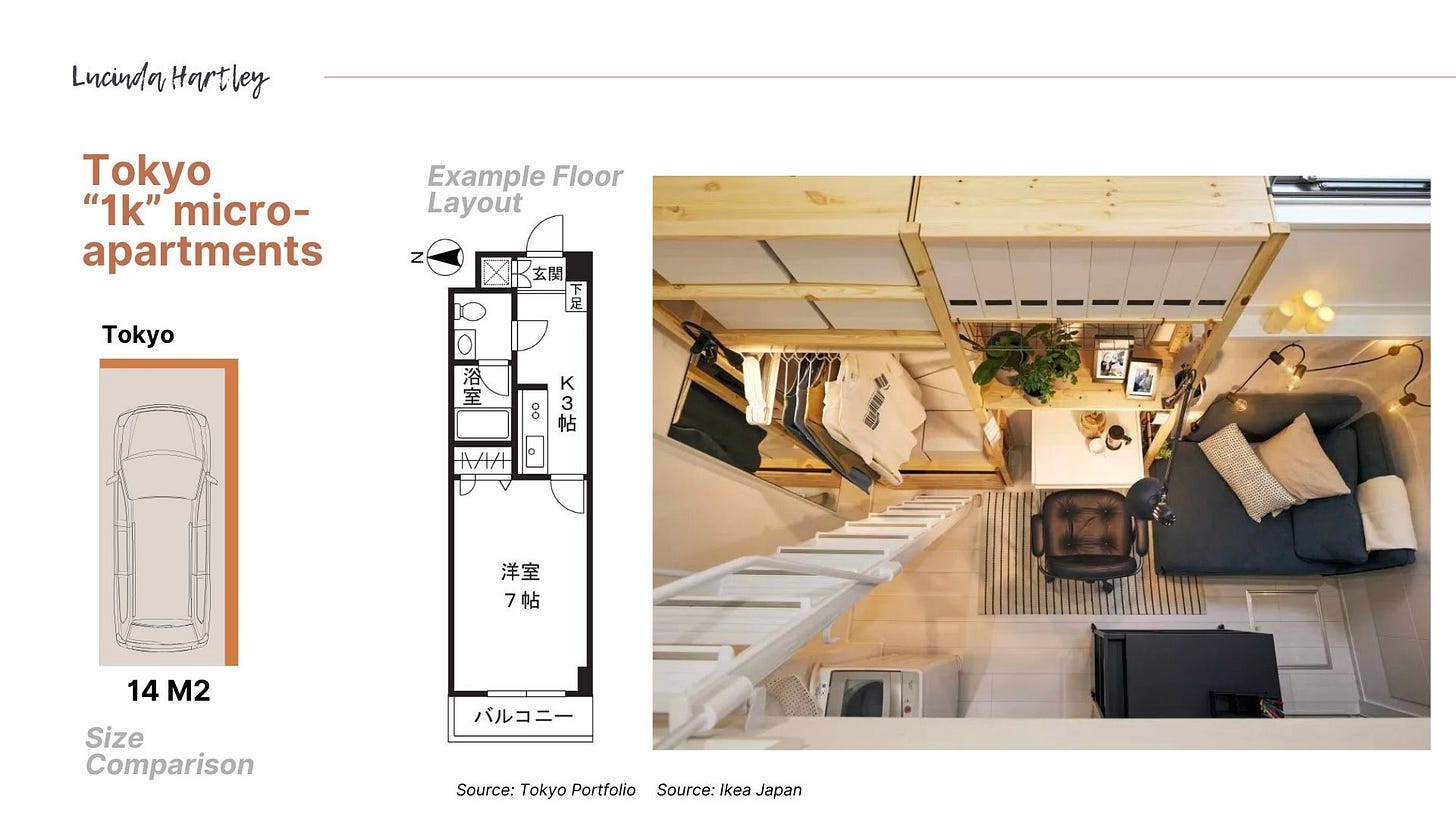

Insight: In Tokyo, studio apartments can be as small as 10 square meters…less than the size of a car parking space.

Read: Family in an apartment? That’s a design problem. There’s a bunch of great resources on designing apartments for more than sole occupants in mind, including families and kids. Check out Cities for Play.

…back to the blog

Up or Out?

We’re all feeling the pain of living in a housing crisis in some way and apartments are frequently touted as a solution. Building up, rather than out. Making the most of existing transport etc.

In theory, yes. It’s cheaper to build up, we need to live higher density to justify services and transport. But why are there so many awful apartments that most of us wouldn’t dare go near. If density is going to be the solution, apartment quality, size and design must get a whole lot better.

How much space is enough?

If you’re struggling to understand what ‘good’ looks like for apartment design you’re not alone. Countries take vastly different approaches. Some have a minimum room size (e.g. Italy, France) others have minimum space per person (Japan), others have no limit (England Denmark) but rely on design criteria instead (like natural light and outdoor space).

In Tokyo, there are legal micro-apartments as small as 10m2, and in Paris as small as 9m2 - or less than a car park area. A recent rental in Manhattan touted as ‘New York’s Smallest Apartment’ was advertised at $1400/month for just (50 square feet).

Many cities don’t impose a minimum apartment size, including Melbourne, Tokyo and Singapore, but here’s a few that do for reference.

Minimum size for a studio apartment

The minimum apartment size around the world varies significantly. Some examples of minimum apartment sizes for a studio apartment are:

London 37m2

Sydney 35m2

New York 30 m2

San Francisco 14m2 (160 square ft)

Hong Kong 11.4m2 (123 square ft)

In Australia, the Victorian Government has been under fire for its apartment standards which have been subject to a parliamentary inquiry. In Victoria there is no minimum size limit, unlike NSW, SA or WA. The inquiry calls for minimum apartment size and accessibility standards. It also calls for tighter sustainability rules around areas such as access to sunlight, ventilation and green spaces.

More than physical space

Most apartment guidelines only talk about minimum space, few go beyond the basic human need for shelter to consider the physical and psychological well-being of the residents. And this is the problem. Small (or smaller) might be ok if there was sufficient provision for light, green space and shared amenity.

Health Implications of Small Apartments

Living in smaller apartments can have significant health implications. A study from Macquarie University highlights the loneliness that can be exacerbated in high-rise living environments. The lack of natural light, limited open space, and feeling of isolation in smaller apartments contribute to this.

Addressing the Housing Crisis: Is Smaller Better?

While smaller apartments might seem like a practical solution to the housing crisis, especially in urban areas, the question remains: at what cost to the mental and physical health of the residents?

The trend towards smaller apartments, as exemplified by the Merri-Bek development, raises important questions about urban living. While they offer a potential solution to housing shortages, it's crucial to consider the long-term impacts on residents' well-being. Urban planners and policymakers need to strike a careful balance, ensuring that our cities remain not just efficient, but happy and healthy places to live.

Comparing between countries can be a bit dangerous as there can be differences in how people access services and to ensure a like for like comparison. A small apartment size might be acceptable (within limits) if you also have access to a lot of common areas / outdoor space as part of the development - but if you get no additional services, the same sized apartment is not acceptable at all. I assume a 9m2 apartment in Paris includes communal toilets and showering facilities which are not an acceptable feature in Australian apartments.

This is very relevant to some thinking I have been doing. I'm designing a linear city. Obe theoretical example would be one block wide and 60 km long. One advantage of such an odd shape is that farm lands could be right next to the city. Well, any ethical person would want the farm workers to live in the city. What if they are very poor? My first thought is that they would live in very small apartments. I'm sure one could get into subsidies, and there may well be subsidies, but my first thought is SMALL.

Obviously the construction quality should be the same as the rest of the city. The way to make it cheaper is to make it smaller.